Holding Students Accountable

If students come to your class unprepared, with readings and assignments not completed, you’re faced with a dilemma. You can’t do the activity or engage in the deep discussion you planned for class time, since that requires that students have done the reading or otherwise prepared for class. On the other hand, you don’t want to lecture over the material you expected them to prepare, because this simply teaches students that they don’t need to prepare for class in the future.

So how can you ensure that your students come to class prepared? The answer is to hold students accountable, with low-stakes “accountability tasks.” Assigning an accountability task helps ensure that all students can participate in and benefit from in-class activities that will help them learn course content.

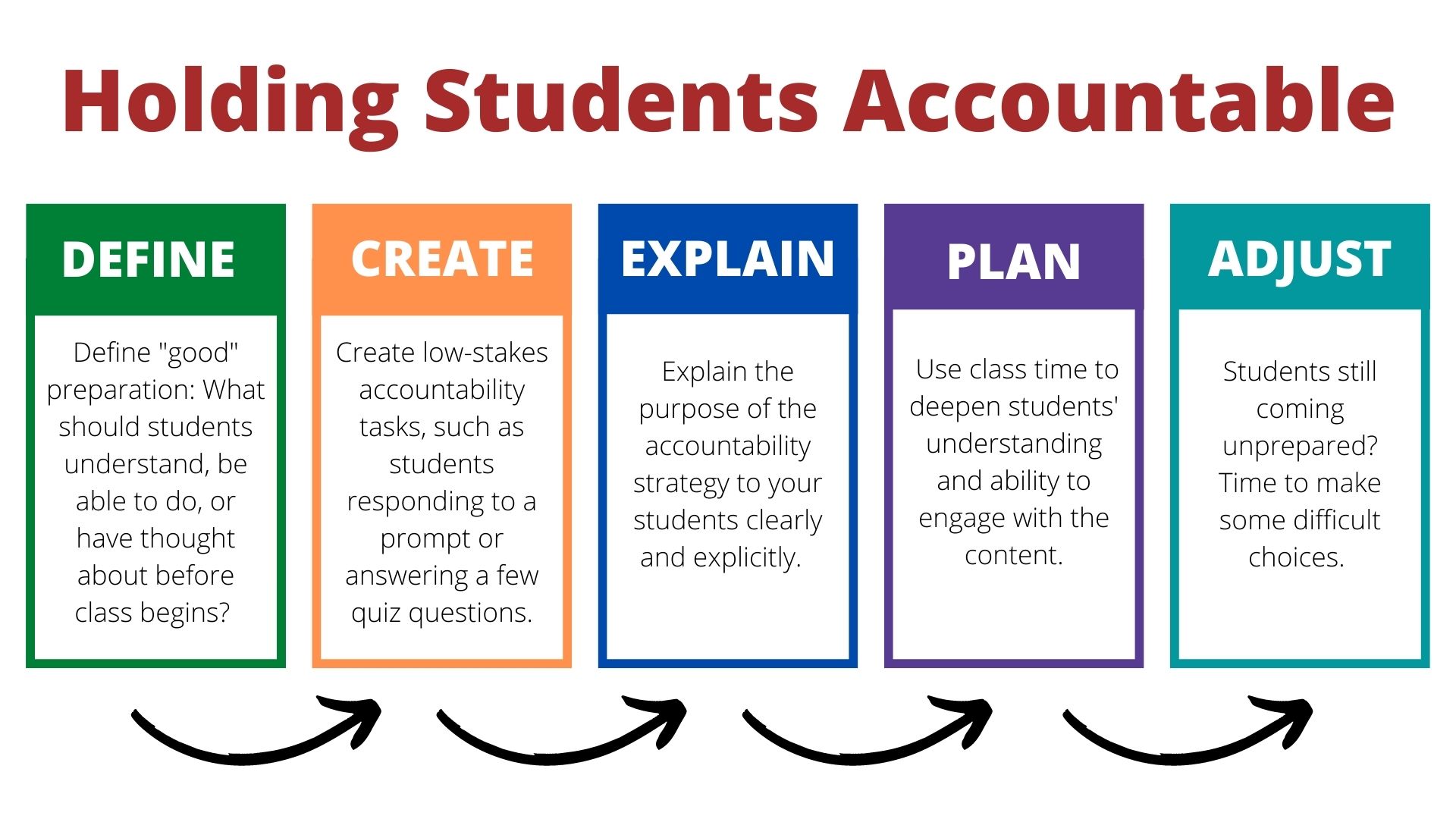

If a strategy for holding students accountable is to be effective, some planning is required. We present this model below.

Define what “good preparation” looks like in your class.

What should students understand, be able to do, or have thought about before class begins? Make sure your expectations are reasonable by thinking of class preparation as students engaging in lower-level cognitive tasks in Bloom’s Taxonomy (recognizing, remembering, or understanding new material). Then in class, students are prepared to engage in higher-level activities.

Create a low-stakes "accountability task"

Accountability tasks can ensure that students have prepared appropriately. The task can be small—writing a couple of sentences in response to a prompt, or answering a few quiz questions—but it should be worth a point or two. Decide whether students will do the task in class or before class. See the list of tasks below for some suggestions.

Explain your accountability strategy to students.

- Explain the purpose of the assignment – that is, why you’ve assigned a particular reading or task. This article about transparency explains why it’s important to explain to your students the connection between the assignment and specific upcoming in-class activities as well as overall course goals.

- Make your expectations clear by explaining specifically what “good preparation” looks like. For example, if you ask students to be prepared to discuss a reading, video, or other source of content, what exactly should they do? Should they extract primary ideas or arguments? Connect ideas in the reading to previous content? Simply learn facts and definitions? The clearer you can be in what you want or expect from students, the better your students can prepare.

- Tell students how your accountability task will help them learn. Make explicit the link among the accountability task, participation in class, and success in learning course content.

- In courses based on readings and in-class discussion, accountability tasks often allow students to practice skills required for major course projects (such as summarizing a text or identifying an author’s main argument, as preparation for a longer research paper).

- If the accountability task is a quiz, tell students about the beneficial effects of retrieval practice on learning. Retrieval practice (also called the testing effect or test-enhanced learning) is the widely accepted finding that the act of recalling facts or concepts from memory (as students do in a quiz) improves long-term retention of those facts or concepts. Frequent quizzes are a form of retrieval practice and thus enhance students’ long-term retention of the material. (This article on test-enhanced learning outlines the research supporting the benefits of retrieval practice.)

- A related rationale for accountability tasks is the spacing effect (also referred to as massed versus distributed practice). Research on the spacing effect shows that retention of information is better if the information is learned in several sessions spread out over days (as opposed to crammed into a single long session). Keeping up with out-of-class reading and assignments is a form of distributed practice, which will make studying for exams easier later on.

- Tell students that holding them accountable enables you to gather feedback about their understanding of course material, which can in turn shape what you do in class. Making this point explicitly to your students helps them understand their responsibility in the learning process.

Plan the class session to include activities that depend on coming to class prepared.

Consider what level of understanding or competence you expect students to achieve from their preparation. Begin the class session at that level and use class time to deepen students’ understanding and ability to engage with the content.

- If you expect students to merely recognize terms or concepts from a reading but not necessarily fully understand them (e.g., a textbook reading for a STEM class), then use class time to help students make sense of the terms and concepts and show how they are connected or applied.

- If you expect students to have a solid (but perhaps basic) understanding of the content, then assume that level of understanding (or confirm it with a brief exercise) at the beginning of class and move on to more complex activities that build on students’ preparation, such as examining a case study, evaluating hypotheses, analyzing a phenomenon or situation, or debating pros and cons.

For example, if students are assigned to read an article with an accountability task is to write two sentences describing the author’s main argument, don’t spend time in class telling students what the author’s main argument is. Instead, start class with a brief activity in which students state the argument and come to a consensus; then spend class time on more complex activities, such as debating the pros and cons of the argument or connecting it to other course content.

If your accountability task requires students to identify things they don’t understand in what they’ve read, spend class time providing additional instruction on the points of confusion.

What should you do if students still come to class unprepared?

If you try some of the strategies listed below and you still see unprepared students in your class, you may need to review your overall strategy and consider some difficult choices. Here are some options to choose from.

- Take some time to gather data. How many students are unprepared? Is it the same few students, or different ones each time? Are they unprepared only on certain days? Once you’ve gathered this information, have a conversation with your class, if many students are coming to class unprepared, or with the unprepared students individually, if there are only a few. Sometimes all it takes is a conversation with a few unprepared students to find out whether they’re having problems outside of class that interfere with their work. If most of the class is unprepared, you might reiterate your justification for the importance of coming to class prepared. You might also need to listen to the students’ explanations and review your task and your expectations.

- Review the preparation you expect students to do, and your accountability task. Is the preparation too difficult? Does the task need to be more clearly organized or better justified? Is the connection between the preparation and in-class activities unclear? Are your expectations regarding students’ preparation unclear?

- You may decide to proceed as you planned with your in-class activity, even if a few students are unprepared. Refusing to switch to lecturing on the material students did not prepare shows students that you’re serious about preparation. Make sure you talk explicitly with the prepared students about how their preparation enables them to complete the in-class activities more effectively or efficiently.

- You may decide to re-think your attendance grades, to count “completing accountability tasks” as part of an overall participation grade. You can also give students a limited number of “oops tokens” at the beginning of the semester. Each “oops token” allows a student to come to class unprepared on one day. Allowing your students to use “oops tokens” recognizes that life happens even for the brightest, most motivated students.

- In some situations you may be able to tell unprepared students to complete the accountability task during the class session. If the rest of the students will spent the class session working in small groups, for example, you can have the unprepared students sit together and complete their accountability task while the rest of the students work. If they complete the accountability task before the class session ends, they can join their group to work on the group’s in-class task; otherwise, they will need to complete the in-class task on their own time. And in either case you can choose not to give the unprepared students “participation points” for that day’s class.

- You may be tempted to simply kick unprepared students out of class or cancel class entirely if most of the students are unprepared. While this is an understandable (albeit emotional) response from the instructor, it doesn’t allow the ejected students to learn; in addition, it may reward exactly the behavior you’re trying to prevent. Instead, you might try one of these in-class activities that work with unprepared students.

There are many different specific tasks that can be used to hold students accountable; some are done outside of class, while others are done in class.

Accountability Tasks To Do Before Class

- Reading check: A brief writing task that can not be completed unless students have done the assigned reading. The assignment can involve a simple prompt (e.g., summarize the main points of a reading) or can be structured as a “worksheet” for easy grading. Students can turn in the response in Canvas or post it in a discussion board.

- Write questions: An assignment that requires students to formulate questions about the reading. These can be questions they would expect to see on an exam covering the reading (perhaps including page references), or questions they would like the instructor to address in class.

- Short quiz: A quiz consisting of a few basic questions about a reading or assignment, administered using Canvas Quizzes or Quick Check. This is a particularly useful strategy for checking comprehension of terminology or basic facts. A related strategy would be to embed questions in PlayPosit videos that students are assigned to watch outside of class.

Accountability Tasks To Do In Class

- Entrance ticket: Brief writing on assigned readings similar to a reading check, but brought to class rather than being turned in beforehand. This can be useful if the responses are complex and students will need to refer to them in class, or if students will be allowed to revise or supplement their entrance ticket response during class. If this strategy is adopted, the instructor will need to decide ahead of time how to deal with students who come to class without their entrance ticket. (You might have them complete the task in class; see point 5e above.)

- Muddiest Point: Students identify specific parts of the content they don’t understand. The instructor can give examples of the most productive ways of indicating confusion, such as asking “why?” questions, or saying, “I don’t understand _________ because __________.” The questions can be brought into class, or posted ahead of time in a discussion board. The class can choose the questions they want the instructor to address, or the instructor can select topics to provide additional instruction on.

- In-class quizzes, using student response systems (Top Hat) or Canvas Quizzes in class.

- In-class activities designed to require students to have done the reading in order to successfully participate in them.

- Some in-class discussions can serve this purpose if it is possible to ensure that all students participate.

- Students in small groups build a concept map based on readings and in-class content.

- Students come up with an example or application of a concept, post it around the class; then do a gallery walk and upvote the best ones.

- If content is two opposing sides of an issue or 2 competing interpretations of a topic, do a continuum dialogue: designate one side of the classroom for strong supporters of one viewpoint and the opposite side for strong supporters of the other. Have students decide which side they found more convincing and line up on a continuum depending on the strength of their conviction. This forms the basis for an informal debate or class discussion.

- Peer accountability—making students accountable to their peers for preparing for class—can be a very effective strategy. Note that when using peer accountability strategies like those listed here, it’s important to be transparent: explain to students why they’re talking to each other. Remind them of the benefits of seeing their peers as valuable sources of information and feedback.

- Peer review: Students engage in in-class peer review of first drafts of their peers’ essays. In this case, if a student comes to class without a draft, you might have them work on their draft in class, and deduct whatever points they would have earned from doing the peer review (see point 5e above).

- Modified jigsaw: For content that can be divided into discrete topics, assign a portion of the class to learn about each topic. In class, create groups in which each member has become an expert on a different topic, and have the group members teach each other about their assigned topic.

- Modified team-based learning: Assign students to teams that are permanent for the semester. Have students take a quiz in class individually and hand it in. Then allow students to take the quiz again in their teams and discuss the questions, filling out a scratch-off form as a team to get immediate feedback on their answers. Each student’s score on the quiz overall is a combination of their individual score and the team score.

Final words

Holding students accountable for coming to class prepared can be a challenge—one that may not be “fixed” simply by using an accountability task. It may take time and a combination of strategies: ensuring strong alignment between assignments, in-class work, and course goals; being transparent about assignments and expectations; not lecturing over content students didn’t prepare; and varying your accountability tasks to maintain students’ motivation. But addressing this challenge will pay off when you see the result: dynamic in-class activities and discussions in which all your students able to engage and contribute.

If you’d like to meet with a consultant to talk about holding students accountable, or any of the other teaching strategies mentioned here, contact us.

References

Bloom’s Taxonomy. Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Retrieved on 7/4/2025 from https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide/blooms-taxonomy.shtml.

Brame, C. J. and Biel, R. (2015). Test-enhanced learning: Using retrieval practice to help students learn Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved on 7/4/2025 from https://derekbruff.org/vanderbilt-cft-teaching-guides-archive/test-enhanced-learning-using-retrieval-practice-to-help-students-learn/.

Elmes, M.R. (2016), They didn’t READ! What to do with unprepared students (besides just kicking them out and canceling class). Blog post retrieved on 7/11/2022 from https://melissaridleyelmes.wordpress.com/2016/02/14/they-didn't-read-what-to-do-with-unprepared-students-besides-just-kicking-them-out-and-canceling-class/

Honeycutt, B. (2016). Five ways to motivate unprepared students in the flipped classroom. Faculty Focus, April 26, 2016. Retrieved on 7/11/2022 from https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/blended-flipped-learning/five-ways-to-motivate-unprepared-students-in-the-flipped-classroom/

Just-in-Time Teaching (JiTT). Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved on 7/4/2025 from https://derekbruff.org/vanderbilt-cft-teaching-guides-archive/just-in-time-teaching/.

Son, L.K. & Simon, D.A. (2012). Distributed learning: Data, metacognition, and educational implications. Educational Psychology Review, 24: 379-391. DOI 10.1007/s10648-012-9206.